Before its mission has even really begun in earnest, the Solar Orbiter, a joint ESA-NASA project intended to observe the Sun for seven years, is already accidentally making discoveries.

The orbiter launched in February, and since then, it has covered about half the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

Its final destination will bring it to within about 42 million kilometers of the Sun, about a quarter of the distance to the Earth. Still, it’s already closer to the Sun than any other solar telescope has ever been, giving it an unprecedented view of the Sun’s surface.

So, while the orbiter was still on its way, the mission’s controllers started testing out its instruments and made a discovery nobody was expecting: tiny solar flares all over the Sun’s surface.

Since dubbed “campfires,” the little flares are among the first images the Solar Orbiter has beamed back to Earth.

“These are only the first images and we can already see interesting new phenomena,” said Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter Project Scientist. “We didn’t really expect such great results right from the start.”

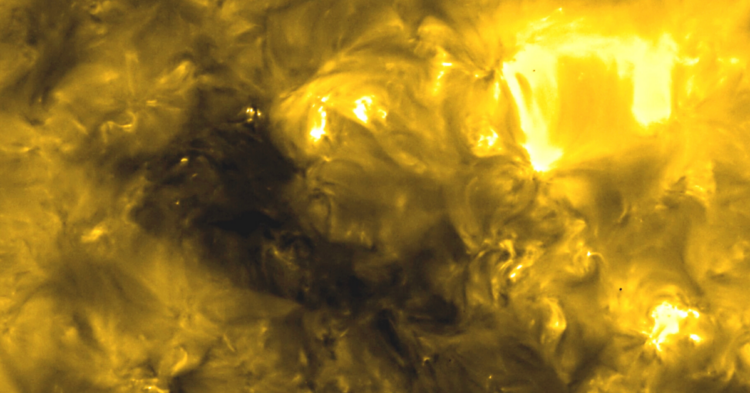

The campfires are really only small in relation to the Sun. As the above image shows, on Earth, they would be absolutely massive.

Solar flares themselves are nothing new, of course.

Huge solar flares have long been observed from Earth. But the existence of such tiny flares was unknown, and as the Solar Orbiter revealed, they’re everywhere .

“The campfires are little relatives of the solar flares that we can observe from Earth, million or billion times smaller,” said David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium (ROB), Principal Investigator of the EUI instrument, which takes high-resolution images of the lower layers of the Sun’s atmosphere, known as the solar corona. “The Sun might look quiet at the first glance, but when we look in detail, we can see those miniature flares everywhere we look.”

Discovering the role all those flares play for the Sun is still something the researchers are unraveling.

At present, it’s believed they may have something to do with coronal heating, in which the outer layers of the Sun maintain temperatures far higher than its inner layers – about a million degrees Celsius versus just 5,500 degrees Celsius on the Sun’s surface.

“These campfires are totally insignificant each by themselves, but summing up their effect all over the Sun, they might be the dominant contribution to the heating of the solar corona,” said Frédéric Auchère, of the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS), France, Co-Principal Investigator of EUI.

The most exciting part for the researchers, of course, is that the Solar Orbiter is just getting started.

It’s set up for a long mission of discovery, both by observing at a distance with six different telescopes, and closer to the spacecraft itself with instruments that can take measurements from things like solar wind.

Having a telescope in space will allow researchers not only a close-up view of what’s going on on the Sun, but also another angle of approach. In 2025, the orbiter is scheduled to shift its orbit to get a look at the Sun’s poles, too.

“If we’ve already made some discoveries with just the ‘first light’ images, just imagine what we’re going to find when we get closer to the Sun, and when we get out of the ecliptic,” said Holly Gilbert, the Solar Orbiter project scientist at NASA. “Very exciting.”

h/t: ESA