It already feels like the 2020 Presidential Election has lasted well beyond what any reasonable person might consider tolerable. The week of November 3 was roughly two months long, amirite?

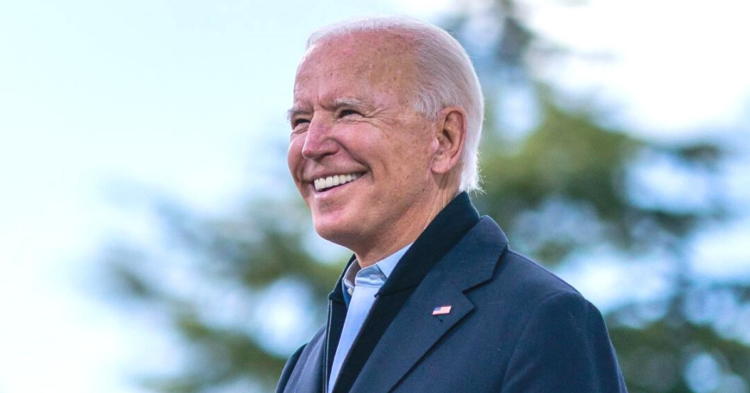

But even though we finally know who the next president will be, there are still many steps in the process to put President-Elect Joe Biden into the White House.

Yes, it has already been a drawn-out process.

That’s 2020 for you. Election Day became Election Week, with a clear winner decided only on Saturday, a full four days after polls opened across the nation.

With record turnout and millions of mail-in ballots — which could be valid with a postmark on or before November 3 despite arriving at polling stations after Election Day — counting took a considerable amount of time, but poll workers got the job done under some of the tightest scrutiny and most stressful conditions the country has ever seen.

But the election is still pretty far from over. Here’s what still has to happen:

Each state must certify its votes.

There’s no set date on when a state’s votes must be certified, but as the Associated Press explained, the governor is required by law to prepare the “Certificates of Ascertainment” documents “as soon as practicable.” Those certificates, bearing the names of the electors and number of votes cast for each candidate, are sent to the archivist of the United States.

The deadline for each state to address and resolve any disputes over the vote tally is December 8. That includes any recounts or court challenges at the state level.

Then there’s the Electoral College vote.

On December 14, each state’s electors — plus those for the District of Columbia — submit their paper ballots for president. 33 states have laws requiring their state’s electors to vote in favor of the candidate selected by the majority of its residents.

Generally speaking, each state’s electors abide by the preference of their state’s citizens and vote faithfully for the candidate who won the popular vote there. But, on occasion, some electors have chosen to go their own way.

State electors who do not abide by the popular vote are called faithless electors.

Faithless electors are rare, with only 156 electors ever known to vote against the winner of their state’s popular vote in American history. And their actions have not been consequential — no faithless elector has ever changed the results of a general election.

In some states, faithless electors can be replaced or face other penalties. In the end, each elector signs six copies of the “Certificates of the Vote” that are then sent to various official agencies including the U.S. Senate. These certificates must be delivered by December 23.

Those electoral votes get officially counted in Congress.

On January 6, a joint session of the House and Senate convenes to count the Electoral Collage votes.

If one candidate receives 270 votes, thus giving them a clear majority of the 538 Electoral Collage votes up for grabs, Vice President Mike Pence declares that candidate the winner.

During that Congressional count, members of Congress have an opportunity to file an objection.

As each state’s results are announced, at least one member of the House and one member of the Senate can make a formal objection in writing.

If it meets certain requirements, each chamber breaks off to discuss the objection for up to two hours, after which a vote will be taken on whether to accept or reject the objection. Objections must be accepted by both the House and the Senate for any contested votes to be thrown out.

If there isn’t a clear majority, things get a bit dicier.

In the case that each candidate receives 269 electoral votes, the House of Representatives instead determines the winner. Each state delegation would get one vote, and the first to 26 votes wins.

However, according to the Brookings Institute , that last happened in 1824. This year, with a clear winner, faithless electors seem highly unlikely to alter the results enough for the House to weigh in, but tensions are high enough that objections may throw a wrench into the works.

Finally, after Congress has had its say, a new president will officially be elected.

Two weeks after that joint session of Congress, on January 20, the new president will be sworn into office on Inauguration Day. It’s a long process that typically plays out in the background, and it has worked out for over 200 years so far.

But 2020 is a year like no other, so it bears watching.

h/t: Associated Press